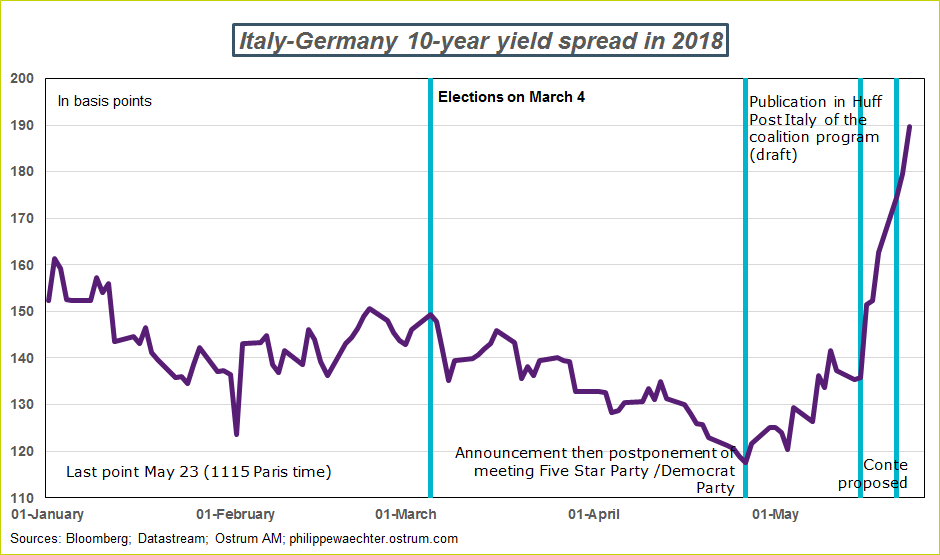

The Italian question remains a concern for Europe, even after the nomination of a prime minister (to be confirmed by the Italian president), who is something of a lowest common denominator between the Five Star Movement and the League. Investors are breathing a sigh of relief, with the yield spread with Germany widening at a comparable pace than last week, as shown in the chart. However, many questions remain.

A number of points are worth raising:

1 – Italian malaise

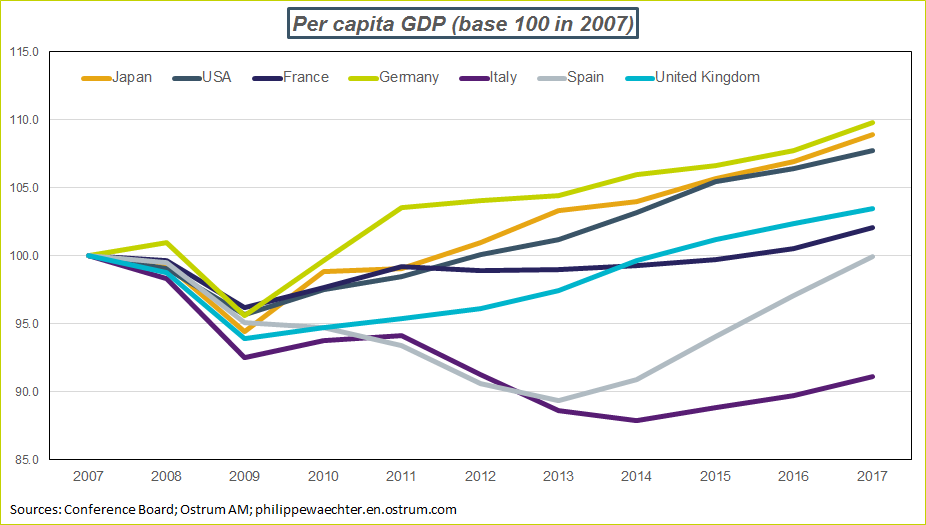

The chart below helps shed some light on the gloom in Italy and the population’s desire to shake up the political scene. Italy has not returned to pre-crisis per capita GDP levels and its performance is lackluster when compared to peers.

Monti’s technical government had sent the Italian economy spiraling into the abyss and Matteo Renzi only just managed to stabilize the situation.

No-one in the country can be satisfied by per capita GDP that is still almost 10% lower ten years on from the financial crisis. Unlike Spain, the Italian economy does not show any internal ability to stage a recovery.

2 – The Italian economy lacks momentum

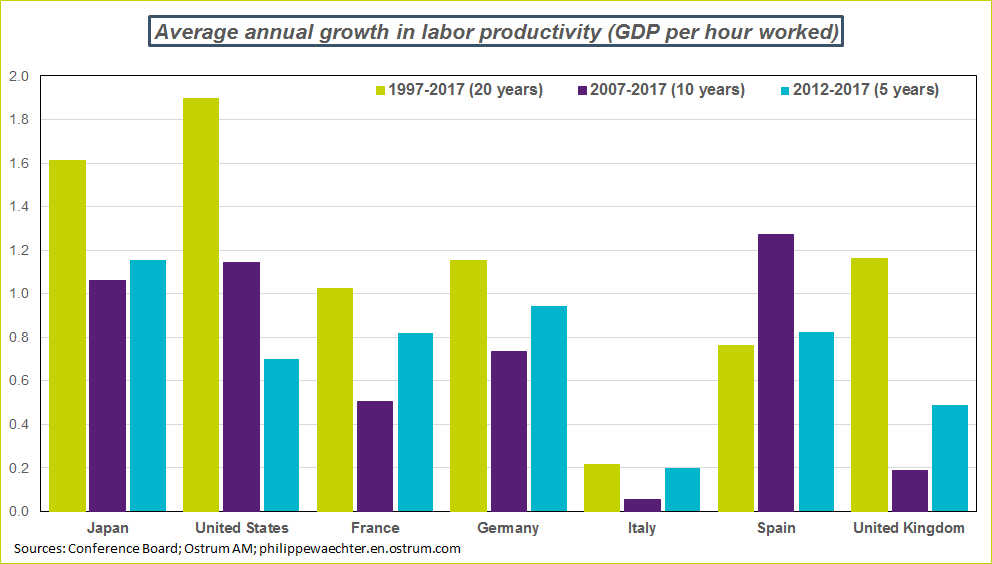

The Italian economy has been in the doldrums for a long time. Productivity saw a shift in trend at the start of this century and meanwhile the population is ageing fast.

The first chart below shows Italy’s very singular productivity profile, with a very different trend across all three productivity gains metrics i.e. 5 years, 10 years, 20 years. Its productivity gains are very weak in absolute terms as well as by comparison with other developed countries. The Italian economy is unable to generate a surplus (which translates productivity gains) to achieve some leeway in the way it manages its economy.

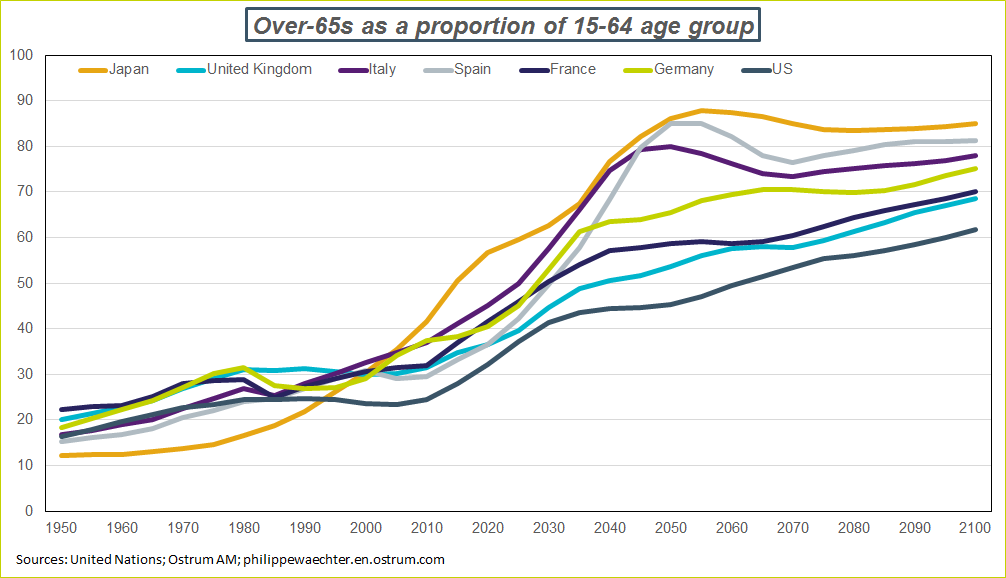

Demographic trends are also worrying as the number of pensioners as a proportion of the working population is poised to increase very quickly over the next two decades. This will lead to a hefty transfer from the younger population to the older population, and younger workers’ productivity will have to make up for the work that is no longer carried out by those who are retiring if growth is to remain on a par with current trends: this will require a long-term shift in the productivity trend, but no-one knows where this can come from. We can see that Italy is shortly to be dragged down by this development, along with Japan, and this will also soon be the case for Spain and Germany.

3 – The importance of insufficient growth in Italy

I draw considerable attention to these macroeconomic matters as the measures taken by the potential new Italian government will considerably heighten the public deficit without breathing fresh life into the economy in the medium term. Medium-term growth is expressed as a function of productivity and demographics, and short-term performances rely on demand. In view of recent trends, the Italian economy is bogged down by its excessively low productivity gains and a dwindling working population.

4 – Economic policy measures

The lowering of the retirement age (which will further amplify the dent from demographics mentioned above), the increase in spending via universal income, along with tax cuts cannot spontaneously be covered by a surge in economic activity. Growth will not pay for these budget costs (3.5% of GDP?), which are here to stay and will drive up public debt, which already stands at 130% of GDP.

5 – The issue of the euro was briefly mentioned in the coalition’s joint manifesto, but it is not set to take center-stage as an immediate measure for the new rulers. However, we should be watchful – an inability to stage an economic recovery in Italy could lead to more radical measures, including a referendum on the euro.

6 – Political considerations, particularly on refugees arriving in the country, set Italy close to Hungary and Poland in their opposition to anything that is not national. This will damage the EU’s united stance by further heightening the differences in views we have already witnessed with these countries. This will lend further weight to the eurosceptic group and hamper attempts for reform in Europe.

7 – The European commission does not have the wherewithal to go against the will of the Italian people.

An excessive budget deficit is not enough to take firm action against the Italian government …and what could the Commission really do to encourage Italy to adopt a pro-European strategy?

This is one of the issues that should be raised at the European Council in late June. How can the relationship between the fiscal policy/monetary policy/economic cycle trio be addressed?

There are three options:

A – option A as defined in particular by northern European countries, which believe that domestic fiscal policy should have the power to address the economic cycle;

B – option B favored by countries such as Germany, which seek greater neutrality for fiscal policy but internal adjustment of the cycle via market and/or control mechanisms;

C – option C, which promotes a fiscal role for Europe or the euro area as a whole, with the option of impacting the economic cycle for the region or a specific country. This is the French president’s preferred option.

The choice between these three alternatives has not been made and the European Council on June 28 and 29 could provide a good opportunity to make this decision. With the possible Italian options, failure remains a possibility and this would provide fertile breeding ground for anti-European sentiment.

The current set-up means that Italy can do as it pleases, with no excessive restrictions preventing it from implementing the program presented to the Italian President on May 21. It is a mistake to think that the Commission will be able to mold the Italian program.

8 – So what happens next?

The first step is that the Italian president, Sergio Mattarella, needs to confirm the nomination of Guiseppe Conte as prime minister, who looks like a puppet whose strings are being pulled by the parties and the power struggle within the coalition.

Next the government will be appointed, which raises the question of the roles for party leaders Luigi Di Maio (Five Star Movement) and Matteo Salvini (League): this choice will have a decisive influence on the policies the government will implement. This government will be a clear reflection of the balance of power between the two parties in the coalition.

The next stage will be the prime minister’s policy statement, which will lay the foundations for government, and this point will be crucial.

The government’s program includes a number of options for loosening budget constraints, whether by increased spending or reduced revenue.

Interest rates on sovereign bonds have admittedly increased considerably, but I do not think that these financial considerations will be relevant in this political watershed scenario: if they were, then the current government would probably be overwhelmed in view of the strong populist vote. I expect a scenario along the lines of the 1981 situation in France where after two years, measures taken lead to an unsustainable path that needs to be corrected.

In other words, all else being equal, the nomination of the prime minister should stabilize Italian financial indicators, which will then fluctuate depending on the balance of the new government’s make-up and its policy statement. If there is no real watershed and Italian populist parties follow in the footsteps of Italian social democracy, then recent distortions should ease. However, if there is a real watershed and an anti-European approach as some parts of the manifesto suggest, then the divergences with other European countries are set to widen.

Philippe Waechter's blog My french blog