World growth stepped up a pace in 2017 as a result of a policy mix that was heavily on the side of demand, while effective monetary accommodation worldwide combined with loose fiscal policy to further drive this recovery.

This extra demand had a positive impact on manufacturing activity in particular, leading to a recovery in world trade.

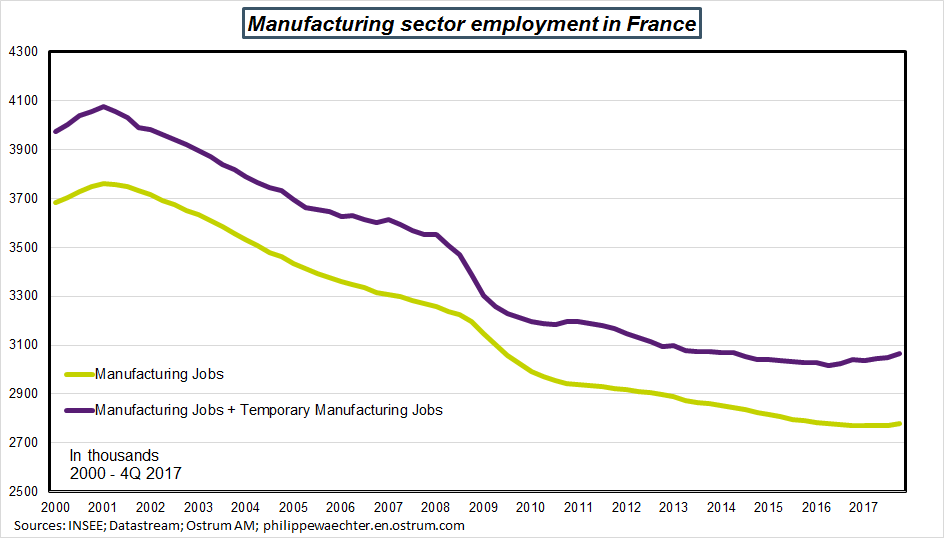

This upswing turned the trend around in the sector in the euro area as well as in France, where job trends displayed a shift, stabilizing and even improving in 2017 after several years on a downtrend, if we include temporary employment in the sector. There was also a knock-on effect on services, pushing up overall activity overall.

But doubts are now emerging on the manufacturing economy’s ability to keep to this solid growth trend.

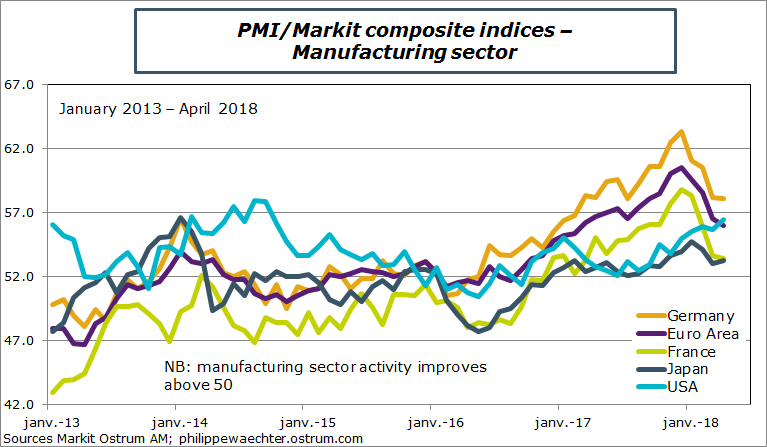

April’s business leader surveys reveal that business in the manufacturing sector has been losing ground for the past three months. It no longer shows signs of acceleration and can no longer act to shore up a faster pace of growth, which is a source of concern.

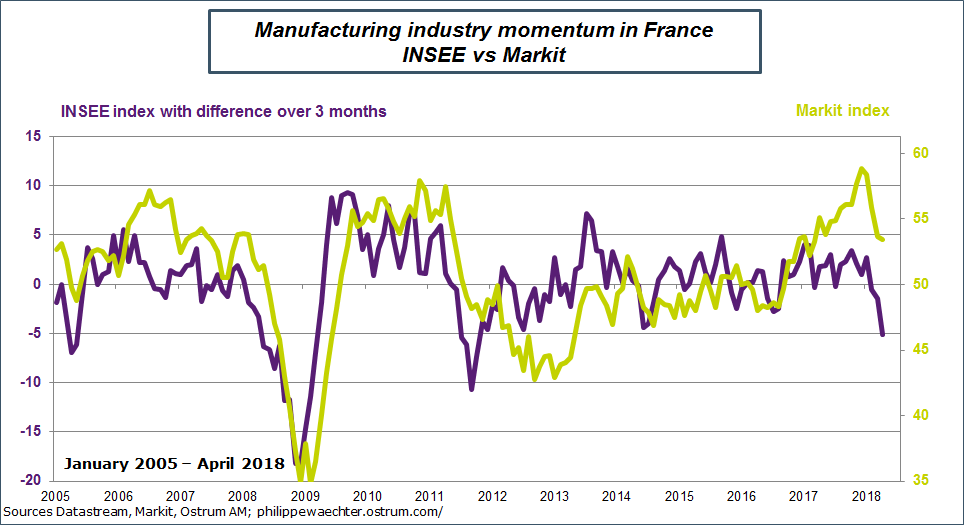

If we look at France, the INSEE manufacturing sector survey reveals a real shift in trend. The acceleration witnessed in late 2017 is now a thing of the past and the chart reveals an impressively abrupt downturn at the end of April.

But this slowdown is not just restricted to France, as the euro area and Germany are also witnessing a weaker pace, while Japan has been slowing over the past three months too. Only the US economy is managing to stave off the downturn. We also note that export order trends are nose-diving across all these countries, apart from the US where it is still robust. In Japan, the index has fallen below the 50 mark.

This fresh situation in the euro area reflects both the manufacturing sector’s inability to operate any faster but also a lack of fresh impetus for this industry. Production capacity utilization rates are near their peak in both the euro area and France and this leads to constraints for companies. In France this also means a failure to recruit as required. Monetary policy had acted as an effective driver in 2017, but it is no longer playing this role as it has remained unchanged for the past several months. Tougher monetary conditions combine with a surge in the euro, in real terms, seen right throughout last year, so the monetary environment is not quite as conducive as in 2017.

This raises the question of whether the euro area economy expanded too fast and was set on an unsustainable trend? If this is the case, then current showings would simply be an adjustment after these excesses. Or are we actually seeing signs of a sharp return to trend? This is the question raised recently by Gavyn Davies in the Financial Times, as he uses an interesting model to suggest that the euro area economy was already sharply returning to its long run growth rate and that the economic upturn is therefore already in the past.

The improvement in monetary conditions since 2013 had driven domestic demand, which boasted robust growth. Private domestic demand growth trends have been stronger since 2013 than in the previous cycle, and this reflects the impact of monetary policy, which aimed at encouraging spending in the here and now, rather than hoarding for the future.

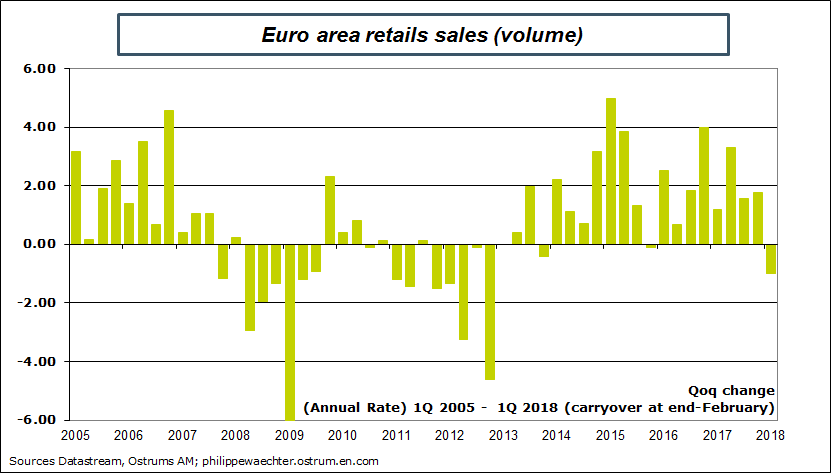

This domestic trend has been undermined since the start of this year. Judging by the first two months of the year, household consumer spending dipped in the first quarter, while investment has also been slipping in France.

This is the first time that consumer spending as reflected by retail sales has decreased since 2013, which is a worrying sign.

In other words, private domestic demand seems to have stagnated in the first quarter of the year. The euro area economy is on a more sluggish trend, supply is restricted by capacity, which the bloc failed to bolster at the start of the decade, and meanwhile demand is flagging.

So we can put forward four conclusions.

The first is that the growth peak is probably already in the past. The second is that demand for credit remains steady despite this, as companies in the area want to use loans to finance their investment, as shown by the ECB’s bank lending survey with banks in the zone. This point counters the argument of an excessively abrupt turnaround in the economic cycle.

The third point is that demand no longer provides the strong support it did in the past, and this should raise questions on wage trends. We are seeing solid job creation but this is having a smaller impact on spending due to weaker wage growth (read here). Internal demand cannot act to counter this trend the way it did in the past.

Lastly, the fourth point is that the ECB must stay on course in this more unsteady economic context, and avoid hampering private domestic demand.

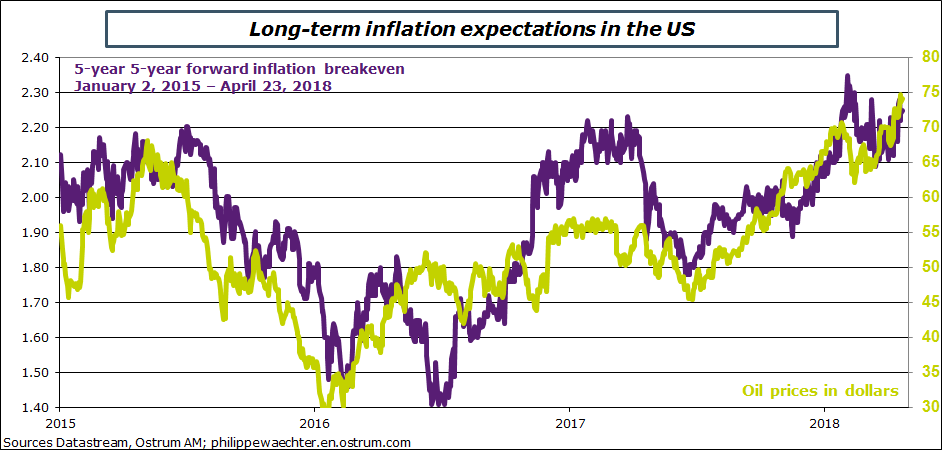

There is one final point worth raising on another issue: rising oil prices must be seen in the context of US measures and sanctions against Russia. Concerns on the likelihood that Russia will maintain its production are behind this price rise, which is reflected by inflation projections witnessed on the markets.

The real question is whether concerns on Russian production are just a blip or if they are longer-lasting. For now, the US looks highly determined, as seen by the example of Rusal, Russian aluminum producer.

Philippe Waechter's blog My french blog